What can original recordings from Stanley Milgram’s famous and controversial ‘obedience to authority’ experiments tell us about cruelty and authority?

David Kaposi, The Open University

ISRF Mid-Career Fellow 2021-2022.

Original image by Alexandra Milgram.

Image is in public domain.

Would you electrocute an innocent stranger if you were told to do so by someone in a position of authority? This is the dilemma hundreds of US adults were presented with in Stanley Milgram’s famous and controversial “obedience to authority” experiments that ran from 1961 to 1962.

As with many social psychologists of his age, Milgram’s formative experience was the Nazi genocide of European Jews during the Second World War. Wishing to understand what had made one of the greatest crimes in human history possible, he devised a series of experiments to find out more about humans’ compliance in the face of authority.

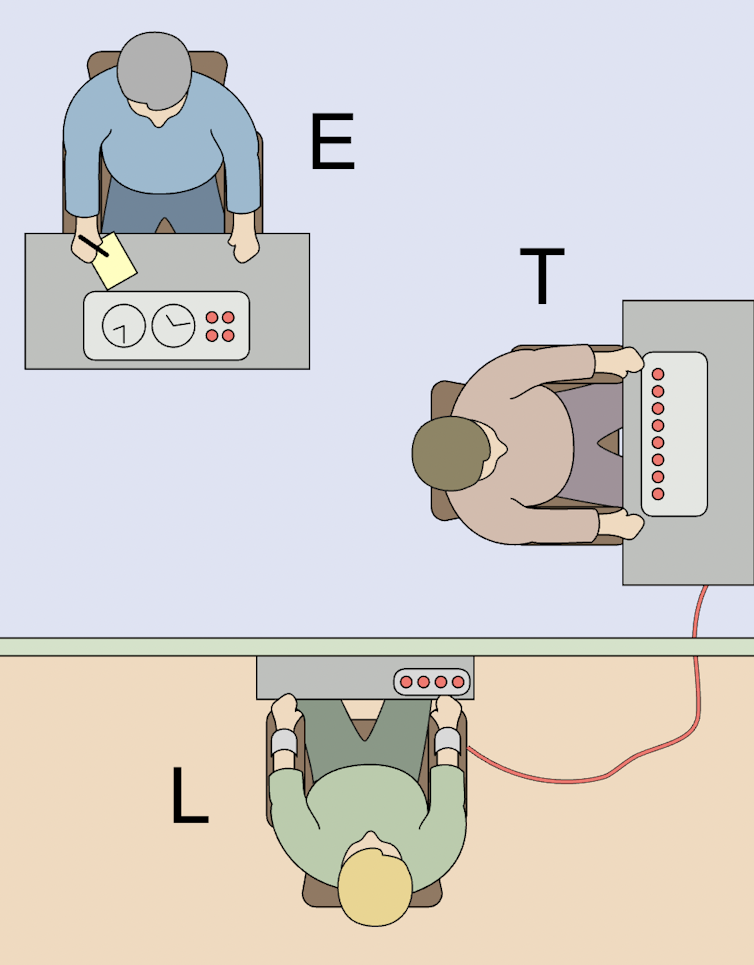

Arriving at Milgram’s lab, a naive participant met another apparent volunteer as well as a lab-coated “experimenter”. The experimenter explained that they were about to participate in an experiment on “memory and learning” and then asked the pair to draw lots to assign one the role of “learner” and the other that of “teacher”. The learner was then escorted into an adjacent room to have electrodes attached to his arms. While the participant, now officially the “teacher”, and the experimenter returned to the room in front of an electric shock generator and a row of switches – ranging from 15 volts (“slight shock”) to 375 volts (“danger: severe shock”) to 450 volts (“XXX”).

A series of word pairs were then read to the learner, whose task was to remember these pairs correctly. The teacher’s job was to “teach” by administering progressively stronger electric shocks whenever the learner did not remember the correct pair.

The shocks were not real: the learner was part of the experiment team and the draw was rigged. Yet, Milgram argued, the vast majority of participants did not show any sign of realising that the real objective of the experiment was not how the “learner” learns, but what happens when the “learner” grunts, then protests loudly and screams in pain, or when he suddenly falls into a deadly silence. Would the teacher continue on the mere say-so of the experimenter? Milgram’s astonishing finding was that over half of them did: “electrocuting” an innocent stranger with increasing severity up to the end of the scale.

Explaining what happened

Milgram was famously never able to match the horror in his lab with an adequate theory to explain it. Up until his death in 1984, he remained preoccupied with the disturbing spectre of his participants’ administering electric shocks while being clearly tormented.

But despite the lack of concrete explanation, as well as outstanding questions regarding Milgram’s method, the experiments continued to be seen as having revealed the truth about humanity and have been used to explain atrocities from the Holocaust to the extreme abuse of Iraqis at Abu Ghraib prison by US soldiers. Continued, that is, until around a decade ago when academics began to interrogate the immense amount of data around the experiments, at a dedicated archive at Yale University.

One popular current explanation suggests that participants stayed in the experiment not because they were simply following orders, but because they enthusiastically identified with the experimenter. Participants, then, were not passive “cogs in the machine”, but motivated pursuers of “evil”, in the supposedly virtuous name of science.

Another popular account focuses on arguments between the experimenter and the participants, suggesting that whether or not the teacher electrocuted the learner depended on the outcome of a debate they had with the “witty” experimenter. It has also been claimed that perhaps participants’ seeming obedience came from the fact they saw through the experimental deception. Or another theory goes that in what amounted to a traumatic situation, participants were effectively coerced by the experimenter into electrocuting the learner.

The tapes

Given the number of current theories, I wanted to find out more about the man who sat in the room with the participants. What was he like? And how did his behaviour influence people’s behaviour? Instead of relying on accounts after the event, I used the audiotapes of 140 of Milgram’s experiment sessions and tried to account for everything the experimenter did.

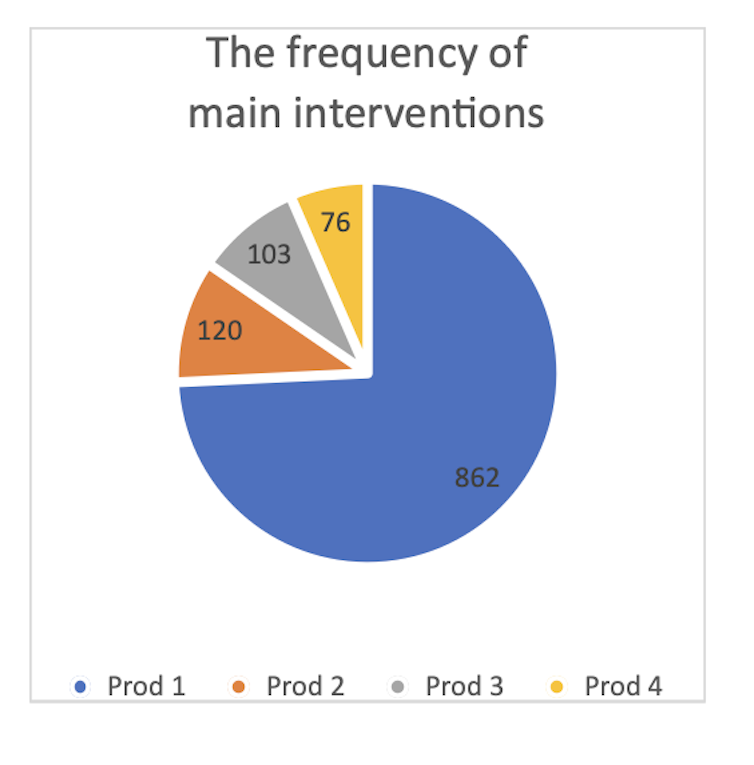

My starting point was what we have always known – when participants resisted, Milgram’s experimenter responded with a succession of four “prods”:

Prod 1: Please continue.

Prod 2: The experiment requires that you continue.

Prod 3: It is absolutely essential that you continue.

Prod 4: You have no other choice, you must go on.

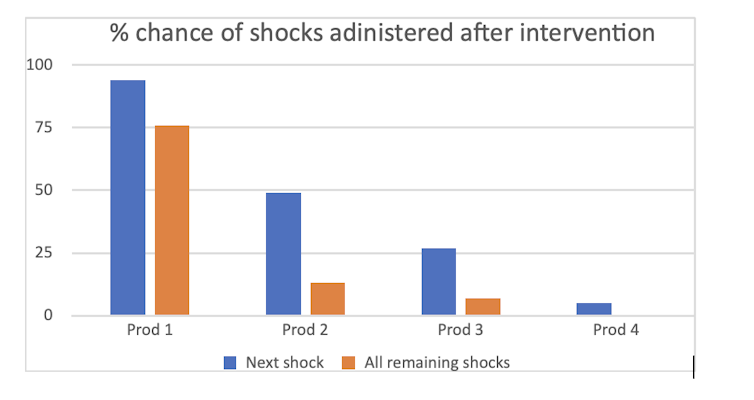

Indeed, the experimenter regularly used these phrases to “prod” participants to continue. But the frequency with which “Please continue” was used was nearly as much as all the other prods three times put together – and it almost always led to participants continuing the electrocution.

In contrast, throughout the 140 sessions, there is next to no attempt from the experimenter either to become a motivating leader or to aggressively coerce participants. And while there are sometimes arguments advanced by the experimenter, they are spectacularly unsuccessful. They tend to lead to participants’ immediate departure from the experiment.

‘Please continue’

But why was a polite little phrase at the very centre of the most infamous experiments in the history of psychology? It’s not easy to answer this question, but let us join “Participant 2010” just as she shocks the learner with 405 volts. After earlier bouts of violent screams, she suddenly encounters an eerie silence:

(The original audio clip can’t be reproduced here. To listen to the audio from the original experiment, go to the original version of this article.)

Teacher: “405 volts.”

[BUZZZZZ]

[silence

– the learner does not protest anymore]

Teacher: “Gold moon.”

[silence

– the learner does not protest anymore]

Teacher: “Hard – stone, head, bread, work.”

[long silence

– the learner does not provide an answer]

Teacher: “Think he’s alright?…”

Experimenter: “Please continue”

[silence]

Teacher: “420 volts”

[BUZZZZZ]

To me, what this shows is that “Please continue” was anything but a polite phrase in these experiments. Not only did it ignore the participant’s worries, it also sought to eradicate any questions or concerns. And I believe that, subtly but relentlessly, the continuous use of “Please continue” worked towards destroying any vestige of humanity from Milgram’s participants.

Milgram’s experimenter was clearly not a bully who beat people into submission. Indeed, the participants inevitably quit the experiment the moment they perceived him to be rude. What participants were astonishingly vulnerable to, however, was the violence hiding in the smallest of his utterances.

Did ordinary US citizens become “torturers” because of an invisible yet relentless assault on them? Maybe they could not stop doing evil, because they did not recognise that evil was being done to them. And this may also be the lesson we can finally draw from the experiments that have haunted psychology for six decades. It is not enough to mean well. The origins of human violence to others may be found in acts that seem barely noticeable.

Dr David Kaposi

The Open University

David Kaposi is a current ISRF Mid-Career Fellow for 2021-2022. He is also a Senior Lecturer at The Open University. As a social psychologist and a psychoanalytically oriented psychotherapist, in his research he seeks to understand violent phenomena with a therapeutic sensitivity to inter- and intra-subjective processes, and joint making and unmaking of meaning.