There is something disconcerting about the Western move to denounce the human rights records of post-colonial states.

DEANA HEATH, UNIVERSITY OF LIVERPOOL

ISRF Mid-Career Fellow 2017-2018

On this 70th anniversary of its independence from British rule, India is being subjected to the sort of assessment that all post-colonial nation-states are forced to undergo on such occasions. How “far” have they come since the end of what their European colonisers liked to view not as a lengthy period of forced occupation, exploitation and violence, but rather of “tutelage” in the values and virtues of European civilisation? Invariably, they are found wanting.

Nowhere is such a perceived lack greater, perhaps, than in the realm of human rights. Post-colonial states are routinely critiqued by Western governments and human rights NGOs for their failure to uphold what are declared to be universal values. Such critiques are often spurred by, and help to reinforce, underlying assumptions about the incivility of racial “others”.

This is not to say that such critiques should not be made. Nor that human rights abuses or attempts to deny them should not be challenged and fought vociferously against.

Take Indian Attorney General Mukul Rohatgi’s recent claim, at the United Nations Human Rights Council in Geneva, that “torture is completely alien to Indian culture”. No less than 591 people died in police custody in India between 2012 and 2015. Torture, sexual violence and disappearances have been practised on a horrific scale by the Indian armed services. The torture and mistreatment of minorities by public vigilante groups, often in collusion with the police and other officials, has become ubiquitous since the rise to power of Narendra Modi and his Hindu nationalist Bharatiya Janata Party three years ago. Given all this, such a claim is clearly grotesque.

Western torture

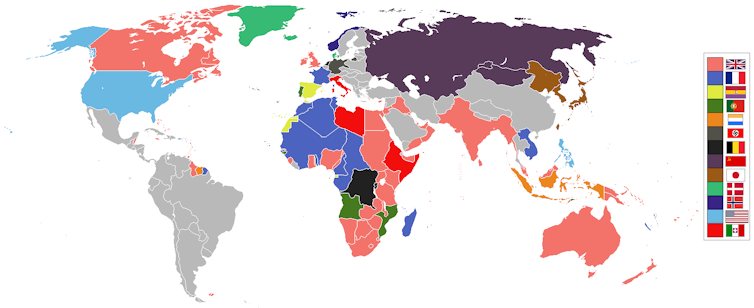

But there is something disconcerting about the Western move to denounce the human rights records of post-colonial states. After all, similar assertions about the purported lack of civility of non-Western peoples were central to the justifications made by European colonial states for their conquest and colonisation of vast swathes of the planet. And since then, innumerable “interventions” have been made in formerly colonised regions of the world in the name of humanitarianism and human rights.

Given this, current critiques need to be placed in a broader historical and geographical context. The West’s record is not as rosy as is generally made out.

Torture is generally regarded as a barbaric remnant of the history of the West, long since abandoned, with its contemporary use confined to non-democratic or non-Western states. In reality, it simply came to assume different forms.

When torture as a public spectacle and a means of demonstrating and enforcing state sovereignty began to disappear in the Western world in the 17th century, it became increasingly privatised, assuming new forms. And torture as public spectacle by no means completely vanished. As the history of lynching in the United States or, more recently, the torture of prisoners by American troops at Abu Ghraib reveal, the public torturing and display of violated non-white bodies has continued to be employed as a means of manufacturing and maintaining white racial superiority.

Torture of one kind or another was and remains central to the operation of modern democratic states, as well as to the management of racial others. And so it should come as little surprise that it was ubiquitous in states that were occupied, despotic, exploitative, and organised according to a strict racial hierarchy, in which the rulers had little sympathy with, or understanding of, the ruled – namely in European colonies.

Colonial torture

In the case of colonial India, torture was a standard means of extorting confessions by indigenous police officers who, at the lowest ranks, were often illiterate, and so poorly paid that they were forced to resort to extortion to avoid an existence of permanent semi-starvation. It was also widely used in revenue collection to extract high revenue demands from impoverished peasants.

While officials in both India and Britain claimed to be shocked when torture erupted into scandal, as it did in the mid-19th century and again in the early 20th, its role in the construction and maintenance of British colonial rule was well known from the late 18th century. Although there were innumerable commissions, reports, investigations and parliamentary enquiries dealing with torture in India, the colonial regime ultimately did little to eradicate it.

This is because the colonial regime largely benefited from torture. Torture made the police “a terror to well disposed and peaceable people”, as a deponent to the 1854 Madras Torture Commission observed. This was undoubtedly advantageous for an alien regime that was ultimately dependent on force to maintain its sovereignty. It also enabled the colonisers to displace the blame for torture from their own system of administration to the colonised, in particular to the purported “rapacity, cruelty and tyranny” inherent in Indian “character”.

Of course we should condemn India’s appalling human rights record when it comes to torture, as well as its ongoing failure to ratify the United Nations Convention Against Torture 20 years after becoming a signatory to it. But this should not be done without acknowledging the history of torture perpetrated by Western democratic states, including in contexts such as colonial India. To do so is not only to ignore the genesis of such modern torture regimes, but to perpetuate the racial assumptions that made colonialism possible.![]()

Dr Deana Heath

Senior Lecturer in Indian and Colonial History, University of Liverpool

I am rather a global vagabond; I was raised in both the U.K. and U.S. and received my Ph.D. from the University of California at Berkeley. I thereafter taught at institutions in the U.S., Ireland and Canada, and held research fellowships in India and Australia. I have also traveled widely. I joined the University of Liverpool in 2013 and am happy to have found a place in which I am keen to stay put. I speak Hindi and am a lover of most things Indian – especially Indian food, clothing (the louder the better) and Indian cinema (especially old films from the ’50s and ’60s).