West London music group 1011 have been banned from making music without police permission.

Joy White

ISRF Independent Scholar Fellow 2015-2016

West London music group 1011 has recently been banned from recording or performing music without police permission. On June 15, the Metropolitan police issued the group, which has been the subject of a two-year police investigation, with a Criminal Behaviour Order.

For the next three years, five members of the group – which creates and performs a UK version of drill, a genre of hip-hop that emerged from Chicago – must give 24 hours notice of the release of any music video, and 48 hours notice of any live performance. They are also banned from attending Notting Hill Carnival and wearing balaclavas.

This is a legally unprecedented move, but it is not without context. A recent Amnesty UK report on the Metropolitan Police Gangs Matrix – a risk assessment tool that links individuals to gang related crime – stated that:

I, as the legal advisor, am being asked by the commander whether he may legally kill these humans. I am the judge — he the jury and executioner.

Furthermore, recent research indicates that almost 90% of those on the Matrix are black or ethnic minority.

For young people who make music, video is a key way to share their work with a wider audience. Online platforms such as SBTV, LinkUp TV, GRM daily and UK Grime are all popular sites. Often using street corners and housing estates as a location, these videos are a central component of the urban music scene. But the making of these music videos appears to feed into a continuing unease about youth crime and public safety.

Fifteen years ago, ministers were concerned about “rap lyrics”; in 2007 some MPs demanded to have videos banned after a shooting in Liverpool. UK drill music is only the focus of the most recent crackdown by the Metropolitan police, which has requested YouTube to remove any music videos with “violent content”.

The production and circulation of urban music videos has become a contested activity – and performance in the public sphere is presented as a cause for concern. This is leading to the criminalisation of everyday pursuits. Young people from poor backgrounds are now becoming categorised as troublemakers through the mere act of making a music video.

Tackling ‘gang’-related violence

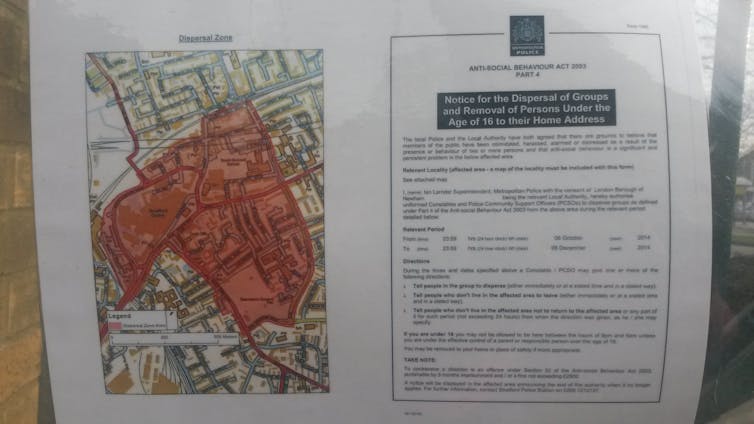

The Crime and Disorder Act 1998 introduced the Anti-Social Behaviour Order or ASBO, a loosely defined term that covers any behaviour, such as playing loud music, littering or drug taking, that is likely to cause harassment, alarm or distress. Local councils and social housing landlords can apply for an ASBO and the breach of an order facilitates entry into the criminal justice system. By congregating in public areas, young people lay themselves open to coming under the watchful scrutiny of the regulating authorities and young people can be served with dispersal notices banning them from public places.

Then, the Policing and Crime Act 2009 defined gang-related violence as actual or the threat of violence that occurs in relation to group activities.

Such “group activities” must be carried out by at least three people who have one or more characteristics that enable them to be identified by others as a group – such as the use of a name, emblem, colour or other characteristic, and an association with a particular geographical area. However, across the public order agencies, there is no agreed working definition what constitutes a gang.

But it is only more recently that some local authorities also sought to remove videos from the internet. In 2013, Newham Council appointed a dedicated member of staff to monitor and remove videos that they felt had evidence of criminal or illegal activity. According to a BBC News report, these videos had a “territorial tone”.

The removal of drill and grime music videos is yet another risk assessment tool in a pre-emptive strategy to maintain public order. But the deep seated and complex issue of youth violence is not solved by gestures – such as banning music videos – that merely give the sense that “something is being done”.

Policing creative expression

In this way, making a music video has become entangled with legislation and policies that are designed to maintain public safety.

Creating a music video to upload share online is an everyday pursuit for many young people. Despite its emancipatory beginnings, YouTube has become a mode of surveillance and intelligence gathering for the regulating authorities. Music videos are now routinely analysed in terms of both lyrics and behaviour, scanned for evidence of perceived wrongdoing.

The desire to secure public safety means that some creative expressions have been deemed to be out of control and therefore in need of being monitored and policed in an authoritarian way. But this has led to a situation where among the regulating authorities, there is little differentiation between MCs using artistic licence to comment on and reference criminal acts, and those that are alleged to be a visual record of actual wrongdoing or an incitement to wrongdoing.

Performance personas adopted by MCs may articulate experiences of life on the margins and, as such, reflect a harshness that is seen and heard in their everyday surroundings. As with other genres and art forms, this creative expression may include fantasy and flights of fancy. One reason why some artists rap about violence is that they come from violent backgrounds – reflecting, not shaping, the reality of teenagers from stigmatised areas.

Nonetheless, young people from such communities are often on the receiving end of policy initiatives and processes to tackle public safety issues. Within this context, any “gang” activity is perceived as an issue of crime and disorder as well as public safety.

The police’s uncritical acceptance of the term “gang” and consequent labelling of groups of young men who gather to make music videos as having a high risk of criminal behaviour means that in impoverished areas, three young men wearing the same colour clothes can be constituted as a gang and therefore become subject to regulation and disciplinary technologies. These policies and practices combine at a local level to criminalise the everyday activities of young people who want to meet up, socialise and pursue their hobbies.

The 1011 case may seem like a proportionate response to increasing levels of youth violence. But the majority of young people who make music videos and broadcast them online are not “gang” members or committing any crime, yet are increasingly rendered as troublesome and subject to growing levels of surveillance and censorship.![]()

Dr Joy White

Visiting Lecturer, University of Roehampton

Joy received her PhD from the University of Greenwich in 2014 and is now a Visiting Lecturer at the University of Roehampton. Joy is the author of Urban Music and Entrepreneurship: Beats, Rhymes and Young People’s Enterprise (Routledge: Advances in Sociology), one of the first books to foreground the socio-economic significance of the UK urban music economy, with particular reference to Grime music.

Joy writes on a range of themes including: social mobility, urban marginality, youth violence, mental health/wellbeing and urban music. She has a lifelong interest in the performance geographies of black music.